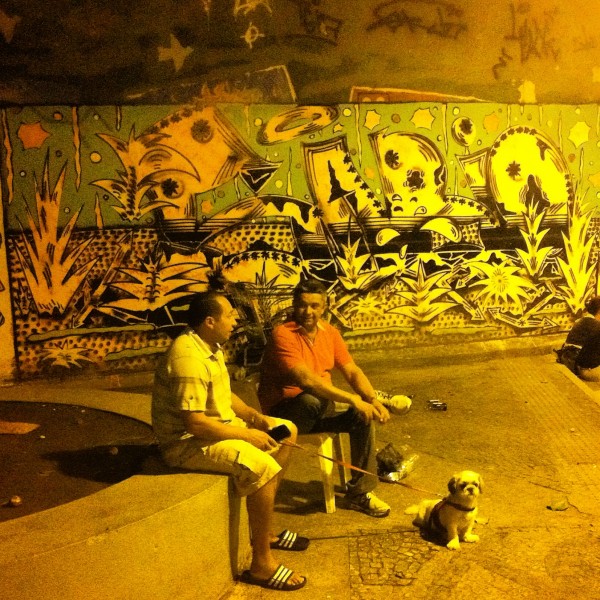

[Photo taken at a teacher’s march in October. “Vandalism is beating up teachers”]

This piece, published this month in the Haldane Society, a British legal magazine, is a follow up to my June piece:

The third consecutive term of the leftist PT [Worker’s Party] government was ticking along relatively comfortably for Dilma Rousseff (ongoing corruption scandals aside) until protests against a bus fare increase in São Paulo triggered similar action across the nation, drawing hundreds of thousands of dissatisfied Brazilians onto the streets in June to protest against a political system they see as corrupt and inefficient. The massive demonstrations came as a surprise to many observers. Brazil is BRICS poster child: a strong democracy and an optimistic emerging economy, ripe for investment and ready for the future. The last time Brazilians took to the streets en masse was back in 1992 to call – successfully – for the impeachment of then President Fernando Collor, the man who froze the nation’s bank accounts.

Rousseff, a former militant involved in organised opposition to the military dictatorship – imprisoned and tortured for her activity – was quick to identify the protests as a sign of the strength of “our democracy” and new “political energy”. The middle class is growing slowly and millions have been lifted out of extreme poverty by social assistance programs initiated by the PT. But as people move laboriously up Brazil’s skewed social ladder, they are hit by the expense of middle class life here, where private health care and private education are standard, given the generally poor quality of public services. In short people might earn more but, while the cost of living rises, they are seeing poor returns from their growing contributions to the public coffers.

Rio, where the largest protests took place, is current focus of national ambition. 300,000 (or one million, depending on who you listen to) came onto its streets on 20th June. Excessive marketing for World Cup preparations and the 2016 Olympics has grated on the population of a city where the cost of living has soared. While there have been notable improvements in public safety, a less violent city is a more expensive city. A principal target of resentment is state governor Sergio Cabral, whose support has plummeted to 8% in his second term of office. Once the initial surge of protests had subsided, demonstrators camped outside his home in the exclusive Leblon neighbourhood until he moved (presumably at the request of influential neighbours) elsewhere. Eduardo Paes, Rio’s mayor, although not unscathed, has weathered the storm with more sagacity, making concessions and inviting protestors for talks.

Although the largest demonstrations were not much short of an outpouring of general discontent, there were some quick victories. Protestors in several cities achieved their immediate goal when local authorities, including Rio and São Paulo, announced a freeze on bus fare rises. In Rio the state government abandoned unpopular plans to bulldoze a school and indigenous museum to make way for a multi-storey car park near the Maracana, future World Cup final venue. Mayor Paes also guaranteed the future survival of Vila Autodromo, a favela that was earmarked for demolition to make way for Olympic development. These achievements seemed unlikely before demonstrators took to the streets.

But while the protestors scored some points, two incidents highlighted the longstanding violence and human rights abuses suffered by the country’s poor. On 24th June, military police belonging to the BOPE special operations unit (portrayed brilliantly by José Padilha in his ultra-violent ‘Elite Squad 1 & 2’ films) killed nine alleged drug traffickers in the sprawling Maré favela complex. One BOPE member also died in this unauthorised operation which left residents without electricity for 36 hours. Then in July members of a police ‘pacification’ unit, based in the enormous beachfront Rocinha favela, took a bricklayer called Amarildo into custody during a routine operation. He has not been seen since. This episode was condemned at the end of August by the Rio branch of the Brazilian Bar Association, which, together with respected local sociologist Michel Misse, launched a campaign to monitor and investigate killings and disappearances linked to police activity in the city. Misse documented 10,000 such incidents between 2001 and 2011. The average of one thousand police related deaths a year in Rio is more than triple the yearly average for the whole of the USA. The national truth commission investigation of human rights abuses under the military dictatorship (1964-1985) counts 540 disappearances for the whole country for that period. Misse’s alarming figures exemplify the class chasm and violence which hamper societal development in Brazil. While the mass marches pointed to the possible existence of a youthful, informed middle class, eager to flex its muscle, the Maré killings and Amarildo’s disappearance confirm that Brazil’s most vulnerable population continues at risk of human rights violations on a daily basis.

On a Friday evening in September I listen to three lawyers who have been voluntarily defending and accompanying protestors detained by police. Carol, Clarice and Natalia tell a story which leaves me depressed. I left Rio for three months just as the protests were beginning, and was enthused by what seemed to be a possible tidal change in public opinion, because for once it seemed that a critical mass of average Brazilians were taking matters into their own hands. I wrote a comment piece for the Guardian where I celebrated the fact that protestors appeared to have avoided attempts by the traditional Brazilian mass media to characterise them as vandals and rioters. Three months down the line it seems that the powers-that-be have succeeded in their goal of criminalising the protestors. Carol tells me that her mother, who leaned out of the window to shout support in June, now sees them as mere troublemakers.

Her mother’s change of attitude appears largely informed by violent TV scenes of clashes as demonstrators face baton charges and tear gas grenades. This began with the dispersal of the massive June 20th march, when military police charged protestors at different points across the city centre. Because of this, the lawers say, the largely peaceful demonstration ended in mayhem. At this point the general public began to dissociate themselves from the protests. I ask about an incident during July. Shortly after the Pope left a meeting at the Governor’s palace by helicopter, a protest outside turned violent. Both demonstrators and police filmed two men in T-Shirts conspiring to throw petrol bombs. Other cinematographers captured images of what appeared to be the same men running behind police lines shortly afterwards. Threatened with arrest, one pulls ID out, waving it at confused ‘colleagues’. These images led to allegations – fiercely denied – that undercover police used violence against other police in an attempt to destabilise the demonstration. Bruno Telles, a 25 year-old student arrested on suspicion of throwing the first bomb, was released when TV images and police statements contradicted each other. It looked like someone wanted to frame him. A backpack containing Molotov cocktails was also found at the scene of the protests. Its owner is unknown. Violent episodes like this led to characterisation of Brazil’s protests as “riots” in the international press (notably The Times).

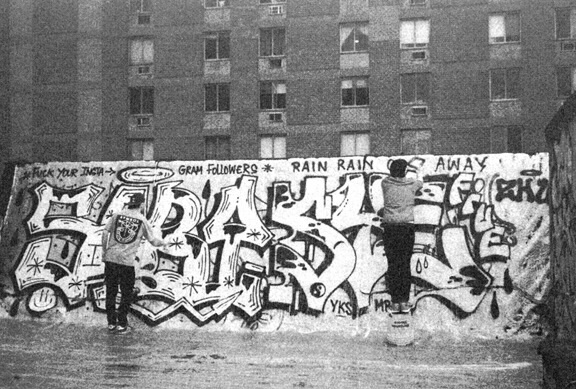

What happened with the episode outside the governor’s palace, I ask? Was it really instigated by undercover police? The lawyers think it might have been, but tell me the investigation was archived. Really? But didn’t anyone follow up? We don’t know, they say, those were the days when the Pope was visiting – so much was going on. Since that moment numbers on the streets have fallen dramatically, down to a hard core of ‘Black Bloc’ anarchist style protestors, who are mostly teenagers. The state governor has introduced a law – unconstitutional, I’m told – to prevent such demonstrators from using masks to conceal their faces. Public opinion is strongly in favour of such a measure: after all, who wants to let vandals gain the upper hand?

Despite recent social advances, Brazil is still a fiercely unequal society. It registered forty six dollar billionaires in 2013, a 25% increase on 2012, according to Forbes. The protests, and the belligerent State response, reflect the contradictory nature of this emerging power. While a new generation struggles to find its voice and millions are lifted out of poverty, corrupt power structures and centuries-old social conflict continue to hinder progress. It is no accident that Fernando Collor – the disgraced former president impeached after the mass protests of 1992 – holds court today at the centre of power in Brasília, where he is Senator. And while everyone knows where to find Collor, no one will say what happened to Amarildo, and neither do we know who threw the petrol bombs at police outside the Governor’s palace.

Note: The month of October saw numerous violent clashes between Black Bloc protestors and police in the context of marches by striking teachers. The Blac Bloc protestors were said to have infiltrated the otherwise peaceful demonstrations. I witnessed both police violence towards peaceful protestors and subsequent Blac Bloc vandalism. Numerous peaceful protestors were arrested under new police powers for dealing with ‘vandals’.