Bate Bola no Carnaval do Rio

Everyone has their own carnival.

Oswaldo Cruz, in the suburbs, feels like another country after Rio’s Zona Sul and its gringos, sameness, endless beer advertising and throngs of inebriated paulistas in fancy dress. Here the streets are quiet and empty, nay deserted. It’s mid Carnival and the only signs of the ‘greatest’ party on earth are the bleary-eyed revelers making their way home. But at the station there is a group of men dressed in the brightest multi-coloured outfits, unlike any costume I have ever seen.

They look like visitors from another planet.

The costumes are designed to make the men appear bigger than they are. They are carrying poles that appear like medieval staffs, and attached to the pole are balls, mini-footballs, that they bounce off the ground. The Bate Bola (also known as Clovis) are groups, mainly youth, who get together for Carnival, and tour the city together. The name Clovis, apparently comes from a mispronunciation of ‘clown’, the word used by the English in the early 20th Century when they first came across the multi-coloured characters at carnival time.

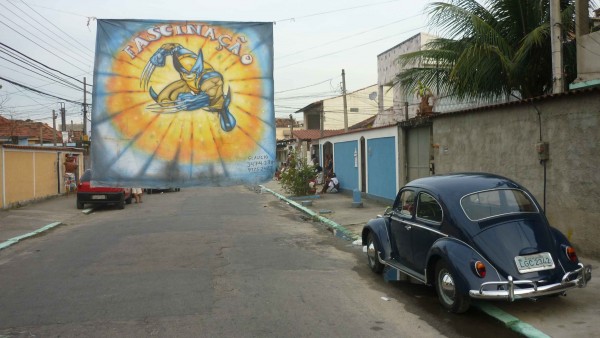

I’m in Oswaldo Cruz to visit Anderson and his Bate Bola turma (group) called “Fascinação”. The residential street where he lives is closed and anything but quiet. A gigantic sound system is churning out loud funk. The friendly and voluminous Anderson – nickname “Buddha” – is under siege in his house, colourful uniforms decorating the walls.

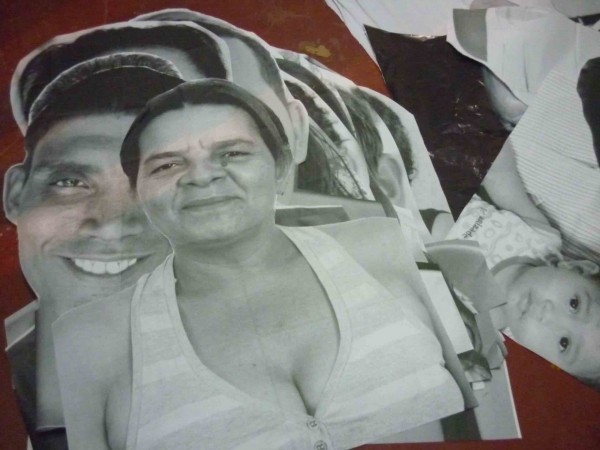

The slogan for this year’s costume is “Quem ta duro já sabe, não se envolve!” which is printed over images of 100 Real notes. It’s a blatant provocation, typical of the zoeira, the way Rio youth wind each other up. “If you’re broke then you already know – don’t get involved!” To wear a Bate Bola costume is an expensive investment. A portion of each month’s wages is saved and paid into an account, to pay for the outfit: printed leggings, T-shirts, gloves, pouches, gear that goes underneath the full costumes which are all gaudy colours and phantasmagoric detail.

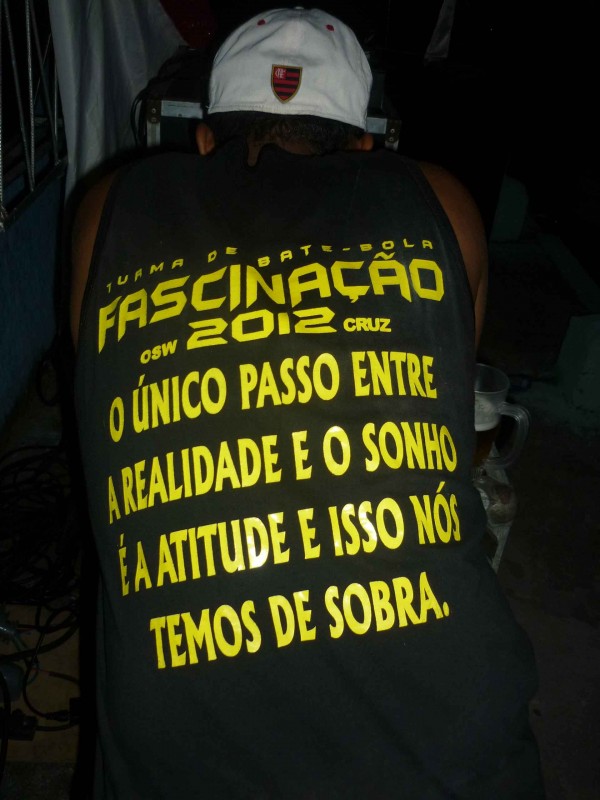

The Fascinação group have Wolverine printed on their undershirts and Magneto on the front of the elaborate costume. The turma also has other t-shirts that have slogans ‘Turma de Bate Bola: OSW-Fascinação 2012-Cruz: O único Passo entre a Realidade e o Sonho é a attitude e isso nós temos de sobra”. The only step between reality and dreaming is attitude and this we have in excess.

Some tough looking guys on motorbikes arrive wearing multi-coloured leggings and identical box fresh Nikes. They’re wearing their masks, pulled back, and therefore sport luminous semi-afros. A group of girls dressed in maids’ outfits hang out across the road. The guys on bikes disappear and reappear half an hour later. They are in the company of a fully dressed Bate Bola who is simply enormous and gets off his bike to bowl down the street, swaying, swinging his full body weight side to side and beating his ball to the ground – CRACK, wack, CRACK!

It’s provocative, and because you can’t see his face, a mixture of play and menace: a clear expression of the thin line between fun and danger, the point where the two merge and one can very quickly become the other: energy, adrenaline and aggression. The rocking side to side, the dancing and the lurid colours and masks resemble a tribal ritual.

The evening moves on and I realize that the visitors are other Bate Bola turmas, come to pay a visit to Fascinação. They sway and swagger up and down the street, first faces covered, then with masks pulled back to reveal the grins behind as they compliment friends and relatives. As each one arrives, the crowd in the street parts in front of them as they surge through – CRACK-WACK – skipping and beating the asphalt.

Fascinação are typical carioca timekeepers and therefore well past the 7pm time set for their exit. At nine preparations are still underway as the front of Buddha’s yard fills with people getting dressed. Kids and friends are kicked out, and only the bate bola are allowed. Outside the street has filled up, with girlfriends, neighbours, friends and sisters. Finally we can see flags emblazoned with 100 real notes above the wall. Dozens of firecrackers are set off and the neighbourhood lights up, smoke filling the road. The music is full blast.

Then the doors are opened and Fascinação and its soldiers of fun spill out all across the road bouncing, flags clutched, swinging their poles and Bola like gladiators of kitsch. They make two or three ascents and descents of the street before pulling back their masks and mingling with their supporters. There are mini Bate Bolas in tiny costumes, and plenty of people taking photos. Mothers, sisters and girlfriends make final adjustment to the outfits. They’re off.

On the way back to the south of the city by van, some teenage passengers break the monotony of the long journey by making wisecracks and targeting pedestrians with a water pistol. But they reserve special admiration for any Bate Bola, who they spot from afar. I ask them what they think of the Bate Bola. One of them responds immediately: It’s the best thing there is. He frowns. But this year, he says with a sigh, “I couldn’t afford it”.

“Quem ta duro já sabe, não se envolve!”