Providência Inside Out

“JR has been a partner in the community since 2008, when he brought his Women Are Heroes project to our hill. When we heard about the Inside Out Project, we knew we wanted to participate. We’re at a pivotal moment in our history. While we have nothing against improvements and development of our city, we’re concerned that the authorities have not included our concerns in their plans. By pasting pictures in the community for the world to see, we’re seeking to participate and make our voices heard in this process. We want visibility, participation and recognition, and the best outcome for this community, which was built by our hands and the hands of our parents and grandparents.” (Mauricio Hora)

Morro da Providência looks over 360 degrees of Rio de Janeiro, giant emerald green papier machê mountains that drop into a city that rolls away into skyscrapers, favelas climbing up the hills, giant primordial rocks, sprawling suburbs and then the Guanabara bay and the open Atlantic. To see the city from the hilltop is to experience Rio at its dramatic, breathtaking and beguiling best.

Morro da Providência is the place where the word “favela” was first used to describe an informal urban land occupation. The name was given to the hill by soldiers returning from the northeast of Brazil where they had put down a rebellion by a mystic leader called Antonio the Counsellor. In the backlands of Bahia where the battle took place, the soldiers camped on a hill they called favela, named after a spiny, thorny shrub that made their forays through the scrubland dangerous and uncomfortable, as contact with the favela plant made their skin break out in sores and rashes. The defenders of Antonio the Counsellor, protected by leather, had no such problem, as they conducted lethal guerilla attacks on the troops, sent to defend the New Brazilian Republic.

It took four expeditions to finally defeat the rebels. The surviving troops returned to Rio de Janeiro, many with captive wives in tow, and waited by the Ministry of War, which had promised them land to live on. When the politicians failed to deliver, the soldiers and their families climbed up the hill behind the Ministry, and set up homes there. Together with freed slaves already living on the craggy outcrop, they founded the world’s first favela.

Morro da Providência (the name Providência was chosen after other settlements became known as favela too) grew and became known for its samba singers and carnival blocos (street parties) and then in the 70s when the drug trade took hold, it became one of the toughest favelas of all, and a no-go zone for people from the rest of the city.

Last year the police moved in as part of a so-called “pacification” strategy to clear armed gangs out of certain key favelas, as part of the citywide development plans in the run up to Rio’s hosting of the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games. Providência is at the edge of the business district and overlooks the rundown port area. The authorities plan to build the Olympic Press corps building here, and have a vision of turning the port into a futuristic marina.

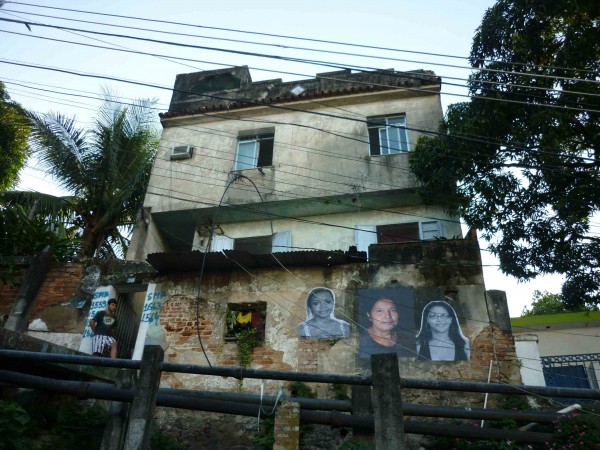

The precarious, perched and sometimes ramshackle construction of Providência is not popular with the authorities, and it seems like they can’t wait to get their machines up there to knock half the favela down. There are plans to build cable cars, amphitheatres and to open the area up for tourists. The plans have been drawn up with no consultation with the residents.

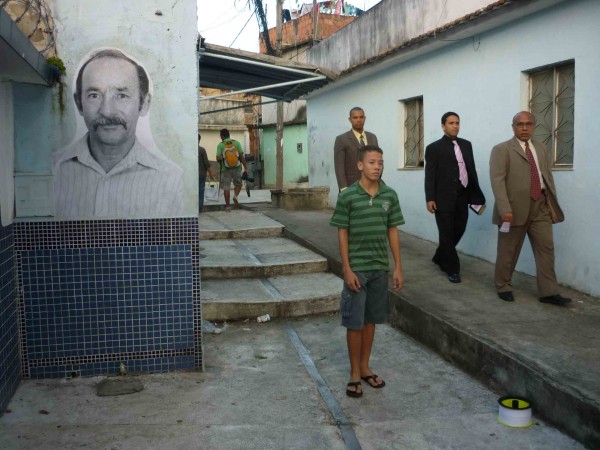

One day a team from the Municipal Housing Authority turned up on the hill, armed with clipboards and blue spray paint. They proceeded to number certain houses with an Orwellian acronym (SMH – Secretaria Municipal de Habitação) and inform those living inside that they were due for removal.

Some residents are not best pleased about this. As Dona Penha puts it “When things were bad, (i.e. when the favela was run by drug traffic and corrupt police) when we had to sleep under our beds at night, and walk our children past dead bodies in the morning, it was fine for us to stay here. Now things are better, we’ve got to go.”

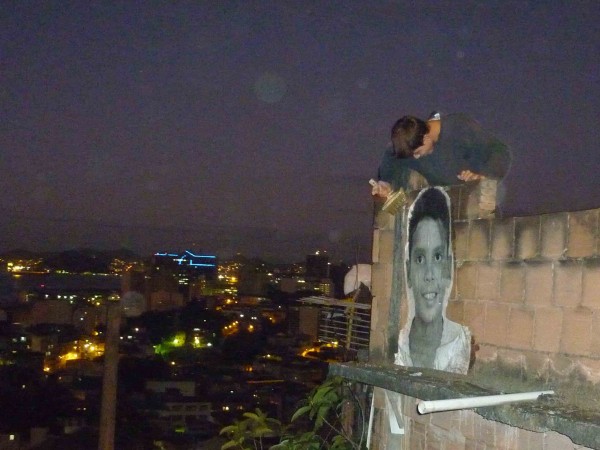

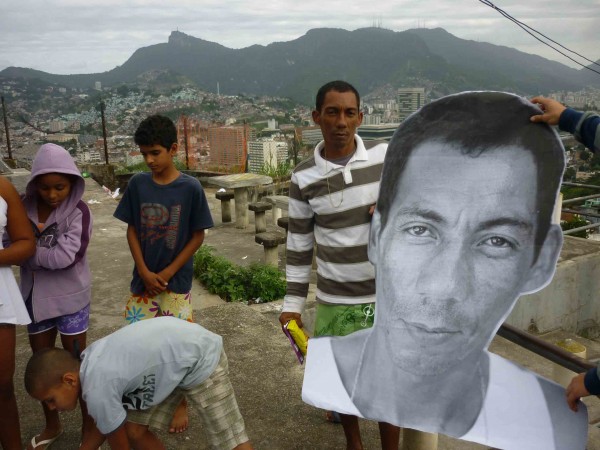

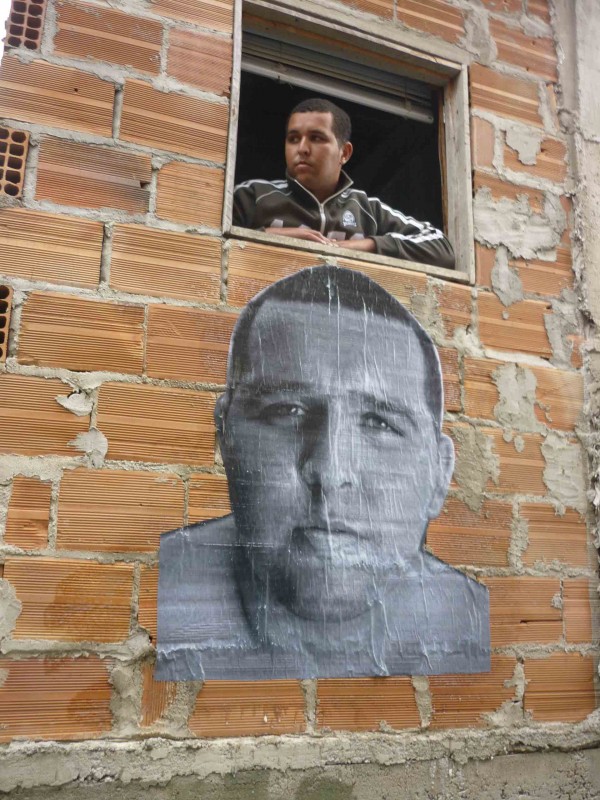

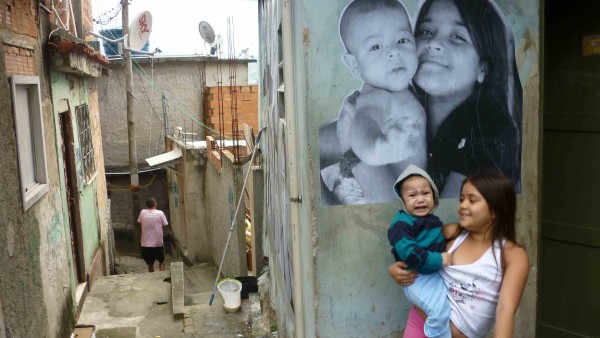

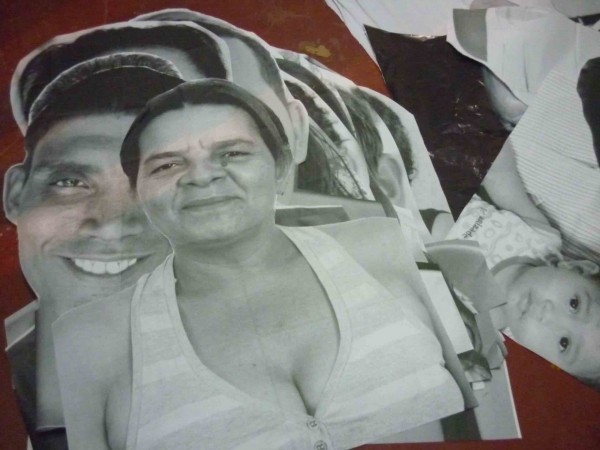

JR’s Inside Out project was a perfect opportunity for people to show their faces. Mauricio Hora, a photographer born and brought up in Providência, took more than 100 portraits of residents that the Inside Out team printed (and hand delivered to Rio, thanks Marc!) which we pasted up with residents over three consecutive weekends.

The first day of pasting saw a visit from Raquel Rolnik, the UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing, that lead to a TV appearance by Mauricio Hora, and it appears that the authorities are already changing some of their plans.

Rosiete Marinho, a community leader, says:

“We’re not invaders, we’ve been on this land for 150 years, and we have a legal right to remain. These photos represent our lives, lives that we want to maintain. We’re not a mere number.”