On The Protests in Rio

A version of this piece, written the night the 3rd large protest in Rio was violently suppressed, was first published by the UK’s Guardian newspaper on 21 June. Hopefully it can help people who don’t really know much about Brazil or Rio to grasp a little of what is happening there.

THE first surprise about the Brazilian protests is that they have taken place at all. The second surprise is their scale. On reflection they should have taken place years ago. The recent hike in bus fares was simply the last straw for a nation tired of being treated like otários [suckers] – as a taxi driver put it to me – by its ruling classes and politicians. Demonstrations in modern Brazil are usually left to small groups belonging to the country’s beleaguered ‘social movements’ and therefore easily discarded by the country’s mass media (in other words the all powerful Globo conglomerate). Protestors depicted as troublemakers, lazy students, leftists, and as rich kids without a cause – by one prominent social commentator in Rio last week – are quickly discredited and forgotten.

This time round Globo and its allies are on the back foot. In Rio, cracks have been showing for some time in the ‘cordial’ facade presented by the city’s leaders to the world. The once popular state governor, Sérgio Cabral, has kept a low profile ever since footage of him engaging in Bollinger Club-style buffoonery in the Paris Ritz emerged in 2012. Images of him cavorting with powerful business associates (known locally as the ‘napkin gang’, because what they sported on their heads during the escapade) enraged a substantial proportion of the electorate. The city’s mayor Eduardo Paes, often recognised as a hard working (if dislikable) politician, has also shown recent signs of strain, becoming involved in an unseemly brawl with an abusive member of the public outside an uptown restaurant last month.

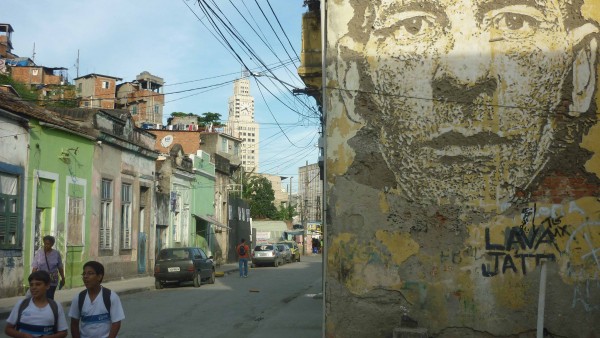

Long uncomfortable hours in crowded sweaty buses on congested roads, and difficult access to substandard public health and education facilities, have been grinding down the patience of easygoing cariocas [Rio residents] for years. A modern but stuffed-to-the-hilt underground service, and an ancient and absurdly overcrowded overground suburban train service do not ease matters. With a soaring cost of living – many prices in Rio are now comparable to European cities – rapid gentrification of housing, and favela removal programs shunting the poor out to the most distant of suburbs, the frustration of large numbers of cariocas is understandable. One friend who visited recently, told me of his amazement at London’s public transport system which is open to all. “In Rio use of public transport is a sign of failure – it’s for people who can’t afford better”, he told me wistfully. Lack of confidence in the city’s public infrastructure is near universal. Anyone who can afford to, takes out a health plan, puts their children into private education and sits in traffic inside an conditioned car. At the very least such fortunate people can stay cool, while figuring out the expense.

Rio’s apparently successful public relations exercise to convince the world of its capacity to change has rested on the much-publicised ‘pacification’ programme. This has seen police take control of some of the city’s most famous and violent favelas. Formerly controlled by heavily armed gangs, communities like Rocinha and Vidigal near the exclusive beach districts, and Mangueira, near the Maracanã football stadium, are now patrolled by young police recruits – bringing homicide rates down to zero in some neighbourhoods. In the Alemão favela complex in the north of the city, this process has reduced the number of bullets fired by police in the region from 23,355 in 2010 to a mere 2,395 in 2012. No one can deny that Rio is less violent today than during any period in the last thirty years.

However the logic behind the ‘pacification’ programme adheres to a long-established practice of placing the poor at the root of Brazil’s problems; sidestepping deep rooted matters of corruption and political inefficiency which contribute to the delay of progress throughout the country. As if by magic ‘pacification’ is alleged to restore Rio to a Peter Pan past of tranquility – a time when genteel samba echoed across the hills, before volleys of automatic weapon fire brought terror and sleepless nights to cariocas in the 1980s.

These protests are proof that Rio’s politicians must do more than militarise the city’s most vulnerable communities to make life bearable for all cariocas, millions of whom live in outlying suburbs distant from the media spotlight. This is why they are so important. By focussing discussion on problems of transport and infrastructure, they are forcing politicians to face difficult questions about how they manage the city. The close relationship between the Mayor’s office and Rio’s bus operators is apparent, but opaque.

Having forced the Mayor to back down over the fare increase, a core of protestors are now calling for a parliamentary commission of investigation into the city’s bus syndicates. By maintaining this focus they hope to prevent the movement from disintegrating or morphing into a nebulous anti-corruption exercise. However the events of Thursday night, and attempts by political groups to hijack the protests, suggest this might prove difficult.

The final surprise may be that Brazil’s politicians are forced to address their conduct of public affairs. Meanwhile, for the taxi driver in Rio de Janeiro, the dream of not being taken for a sucker stays alive.

[….]

Postscript:

THIS piece was written on 20 June and things have been moving fast since then. Today, 25 June, the military police killed some 10 people in an operation in the favela of Nova Holanda. At the same time, the city’s legislative assembly gave the go ahead for the investigation into the bus companies. A sliver of a light on a dark day. What must the Pope be thinking about his upcoming visit?

From comments under the original piece:

I’m brazilian and I’m tired of being taken by stupid. I’m tired of lines in hospitals, with no meds, no infrastructure, no beds, people lying on the floor waiting, i don’t know,for God maybe. I’m tired seeing kids without a good school, good teachers, good infrastructure, helping then to become a citizen and not just another “brick in the wall”. I’m tired to pay the taxes and seeing my country accumulate more than ONE TRILLION in taxes and still, give no return to us, no even the enough. I’m tired of being a clown. We need support from everyone. From anyone who still believe that we can change and be BEAUTIFUL no just for FIFA, not just in the “rich parts”, no just for “english see”, but for us, brazilians too.

Amazing your post! The Globo corporate will never write the news like you did. They will always mask the news, changing the line and making the people believe in something is not true. They are trying to stop us. They are saying this is a violent manifest. But it is not. Is just the loud voice of the people for our rights and justice! Thank you! We live in a fake democratic system. Our people don’t have schools and don’t have hospitals. We live in a corrupt government system that think we are suckers, and steals our money in our face!